The reduction in major business disputes before the Judiciary has been widely discussed among jurists

NUMBER OF NEW ACTIONS ON BUSINESS DISPUTES

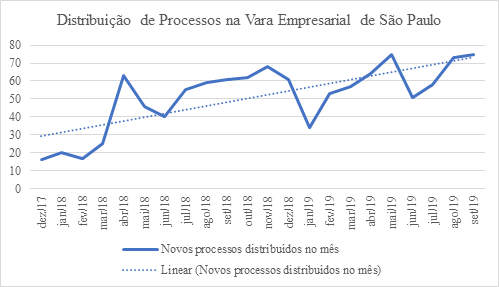

At first, one might think that the disappearance of these major corporate disputes was the result of a reduction in the number of actions in corporate matters — or even the development of other dispute resolution techniques such as mediation. However, this does not seem to us to be the case. Data on the distribution of cases collected by the Justice in Numbers program between the years 2016 and 2018, from the National Council of Justice, reveal that the number of new actions being filed that deal with business matters has been growing in recent years, especially in the states of São Paulo (from 20.452 in 2016 to 37.540 in 2018) and Rio de Janeiro (from 6.114 in 2016 to 18.537 in 2018)[3].

Major corporate disputes – Distribution of Cases in the Business Court

MIGRATION OF BUSINESS DISPUTES TO ARBITRATION

The truth is that major business disputes are migrating from disputed fields. In the United States, the specific laws and the quality of judicial decisions in the State of Delaware have attracted the installation of the headquarters of important companies there, precisely to prevent possible disputes. Among other reasons, the distribution of legislative powers established by the Constitution would not allow this same effect in Brazil. Unlike what happens in Delaware, here arbitration is gradually replacing the Judiciary as the most appropriate method for Brazilian business to resolve cases of greater complexity or value involved.

A survey carried out by the Center for the Study of Law Firms (Cesa) in 2017 reveals that corporate disputes represent a very significant portion of arbitration procedures administered by the main arbitration chambers in the country.[6]. At the Brazil-Canada Chamber of Commerce Arbitration and Mediation Center (CAM-CCBC), corporate disputes and litigation arising from M&A contracts make up more than half of all its ongoing procedures. At the FIESP-CIESP Arbitration Chamber, around a third of its ongoing procedures concern corporate disputes or M&A contracts[7].

ADVANTAGES OF ARBITRATION

Among other factors, the following factors encourage the choice of arbitration: the possibility for the parties to choose who will act as arbitrators of the dispute; the flexibility and speed of the arbitration procedure; and the prerogative of the parties to agree to the confidentiality of all acts carried out during the course of the arbitration.

Voluntarily electing a highly specialized professional in a given matter to decide on the dispute is, without a shadow of a doubt, a relevant attraction of arbitration. Citizens who do not opt for arbitration are necessarily assigned to a magistrate, designated in accordance with the rules of material and territorial competences defined by law and rules of judicial organization, sometimes responsible for dealing with any and all matters of law.

In corporate matters, the processing time for disputes is extremely relevant and potentially harmful to the health of companies. Statistically, a legal case takes an average of 4 years and 4 months to be decided by the state Courts of Justice[8], and it may take a few more years to exhaust all appeals (final decision) if the case reaches the Superior Courts. In turn, arbitration procedures in Brazil usually end in around 1 year and 9 months[9], guaranteeing the parties a final, binding and enforceable decision without review on the merits in more than 150 countries, under the New York Convention.

ARBITRATION AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Due to these factors, the option for arbitration is considered a measure of good corporate governance by the Brazilian Institute of Corporate Governance (IBGC)[10] and by B3, which even requires the inclusion of an arbitration clause in its bylaws as a condition of access to the listing segments of Bovespa Mais, Bovespa Mais Level 2, Level 2 and Novo Mercado.

In the same vein, the reform of the Arbitration Law implemented in 2015 sought to facilitate the access of public limited companies to arbitration, ending an old discussion about the binding of dissenting shareholders to the arbitration clause approved by the majority of voting capital, through the inclusion of a new provision in the Law of S.As. which expressly provides that all shareholders are obliged to submit to arbitration. The Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) also encouraged the use of arbitration by providing, in its Normative Instruction No. 555/2014, the obligation for privately held corporations to include an arbitration clause in their bylaws in order to receive investments from equity funds.

[1] Research cited by Paula Forgioni, Full Professor of the Department of Commercial Law at the Faculty of Law of USP, in a conference given at the Congress Disputes in M&A Contracts, promoted by IBRADEMP – Brazilian Institute of Business Law on 07/10/2019 in the city of São Paul.

[2] In accordance with Resolution No. 538/2011 of the Court of Justice of São Paulo, the Reserved Chambers of Business Law are dedicated exclusively to judging conflicts involving Book II of the Special Part of the Civil Code (which deals with Business Law), the Corporate Law, industrial property, unfair competition and franchise contracts.

[3] NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JUSTICE. Justice in Numbers Database – Demands by class and subject. Available at: , accessed on 5/40/03. The data indicated took into account the set of actions with the subject “Companies”.

[4] Available for download at: , accessed on 27/11/2019.

[5] Actions involving the subjects “Society”, “Types of Companies” and “Capital Markets”. Actions with the subject “Companies” suffered a slight drop in this period, largely due to the decrease in the number of bankruptcies and judicial recoveries (in 2014, 2.916 cases of this type were filed, while in 2018 only 2.499 were distributed).

[6] LAW FIRM STUDY CENTER. Yearbook of Arbitration in Brazil 2017. São Paulo: CESA, 2018. Available at: , accessed on 2017/27/11. P. 2019.

[7] LAW FIRM STUDY CENTER. Yearbook of Arbitration in Brazil 2017. São Paulo: CESA, 2018. Available at: , accessed on 2017/27/11. P. 2019.

[8] NATIONAL COUNCIL OF JUSTICE. Justice in Numbers Report 2019. Brasília: CNJ, 2019. Available at: , accessed on 2019 /08/20190919. P. 27.

[9] Arbitration takes, on average, 1 year and 9 months to resolve disputes in Brazil. Migalhas, April 10, 2019. Available at: , accessed on 17/299336,21048/1.

[10] BRAZILIAN INSTITUTE OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE. Code of Best Corporate Governance Practices. 5th Edition. São Paulo: IBGC, 2015. p. 27.